What is a ringing stone?

Ringing stones, singing stones, bell stones

Most large stones are dead and silent, from an acoustic point of view. But a few stones—which look like other, ordinary stones—come to life and ring when you hit them with a small stone or some other hard object.

Sometimes the sound is metallic, other times the sound is rich and bell-like. Due to the association with bells, these stones are in some cases called bell stones—klokkesteiner in Norwegian. People have also used other words to describe the sound, such as singing stone (syngestein), song stone (sangstein), or just sounding stone (klangstein).

An important part of the local traditions around the stones are the names, such as Syngjarsteinen (The Singing Stone) in Folldal, Dønnsteinen (dønne, from Old Norse dynja, making sound) in Lyngdal, or ‘Steinen som sier pling’ (‘The stone that says pling’) in Fredrikstad. There is no universal or official designation for these unusual stones, neither i English nor Norwegian. In this site we have chosen to use klokkesteiner (bell stones), one of the Norwegian names. The most used name in English, at least for research purposes, seems to be ringing stones.

In the work of registering these boulders, it has turned out that the phenomenon is varied. Some stones at the water’s edge produce a bell-like sound when waves have hit them, while other times stones are linked to church bells through stories and legends. Large boulders producing echo are called ‘singing stones’ because it seems like the stones themselves have voices. Instead of excluding these cases, and concentrating exclusively on ‘real’ ringing stones, we have chosen to include them, under a wider umbrella. We have also registered place names alluding to stones, but where there is no existing, actual stone, of various reasons. Stones and meaningful sound is common to all these cases. Our material – where geology meets cultural history – expresses how people have created meaning in their surroundings.

But what about ringing stones with a clear sound, but without names or without being known by people at all? Are they counted in as ringing stones? At the risk of ending up with unmanageable material and thousands of stones, we have human activity as a criterion. We thus register stones that people know about, that have been used and played, that are associated with stories, legends or traditions, or that have a cup marks, petroglyphs or other archaeological traces that link them to human activity.

There is a concentration of ringing stones in southwestern Norway, with a core area in Dalane, which is Magma Geopark’s area. Apart from this concentration, the stones are distributed throughout the country. We have registered stones in all counties.

When did people start to use stones as sound tools?

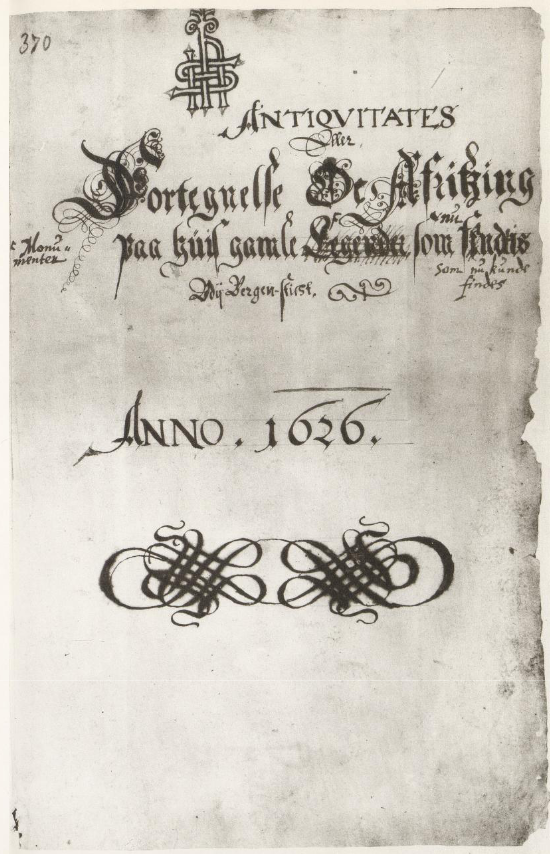

Some ringing stones are mentioned in written sources from the 17th and 18th centuries. The earliest source is a manuscript of the student and priest’s son Jonas Andersson Skånevik, who in 1626 on mission from Ole Worm in Copenhagen traveled around and collected information about ancient monuments in the diocese of Bergen. In his accounts, he writes about a stone on an islet by the rectory in Skånevik that sounds ‘like beating on a piece of ore’. Andersson had grown up at the rectory and has presumably known the stone from his early years.

Another example is Syngjarsteinen (The Singing Stone) in Lom, described in different 18th century sources. The first was Bishop Peder Hersleb, in the report after his visit to Gudbrandsdal prosti in the 1730s. Among other things, he is asked to report information on antiques, and from Lom he mentions only one, namely a ‘large stone, oblong and about a couple of cubits long and wide, which makes a sound like a bell when you strike then with another small stone. It is therefore called the Singing Stone’. It is apparent that Hersleb—and his informants—believed that this was the most valuable antique the village could present.

We do not know when people started to deliberately to make sound on ringing stones. It is unlikely that this is a modern phenomenon; the stones with the right acoustic properties have been in place since the ice age, and it is reasonable to believe that the first people who arrived in the Stone Age, discovered these stones and their sound.

There is no reliable method for dating these stones as sound tools. But by looking at shorelines at different times, it is sometimes possible to determine approximately how far back a ringing stone may have been used. One example is the ringing stone, Klokkesteinen‚ at Aga, Ullensvang in Hardanger, which is located just a few meters above the shore of fjord. Due to the land uplift after the ice age in this area, the sea level has sunk quite a lot. According to a geological analysis, the fjord surface was 9–10 meters higher than today three thousand years ago, 6–7 meters higher two thousand years ago, and about 3 meters higher than today’s level a thousand years ago. Consequently, we can establish that this ringing stone appeared in what is today called Klokkesteinviki by the end of the first millennium of our era. The environment around the stone has several ancient monuments from the Bronze Age and other prehistoric periods, but it was only at that time when Christianity took root that the stone literally emerged from the sea.

Few of the Norwegian ringing stones has a confirmed dating to prehistoric periods, though there has not been much research on this phenomenon. In Sweden, there has been some research, especially at the University of Uppsala. They have shown that many ringing stones can be linked to Bronze Age environments. They often have cup marks—round depressions that are carved into the surface of the stones. This was a common motif in rock art from the Bronze Age, but it is still no safe dating method, because cup marks are known from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages. In one case, however, the Swedish archaeologists were able to date a stone with certainty: The Håga Stone near Uppsala was placed inside of the wall of a Bronze Age cult house. The location makes it plausible that the Håga Stone were associated with the practice of religion.

Placement of ringing stones in the landscape

Maja Hultman, one of the archaeologists who has researched Swedish ringing stones, has paid special attention the stones’ placement in the cultural landscape. Many stones are found in archipelago environments with a clear connection to the Bronze Age coastline. Apart from the proximity to water, a common element is that the stones are located near settlements and in connection with traffic arteries, according to Hultman.

However, it is unlikely that the stones were used in communication and signaling for the travelers, since the sound is weak. The human voice is far stronger, and other instruments would be more applicable for communication over distances. It is more probable that the stones were used on special occasions, perhaps in ritual contexts.

But what kind of ritual activities could be relevant—in the distant past? Both Maja Hultman and others have highlighted varp as a key word. Varp, a sacrificial throw—like hermes in the Greek tradition—means that travelers in certain places stopped and threw stones, coins or other small objects, as a kind of sacrificial act, to mark an event, or to pray for happiness on the journey. In our case, we can imagine that stopping and pinging on a ringing stone meant a wish for happiness, as a magical and ritual act.

In an article about the before mentioned Syngjarsteinen in Lom—which is located in the mountains by an old country road—Lars Rusten writes about such a function: ‘Maybe this was about the same as a “varp” they should not pass before they had thrown a stone on the varp, but in this case that they have knocked on the stone and got a tone, as wish for the journey … Those who passed by here probably had many kinds of errands, and then one must believe that such a bright sound and tone from Syngjarsteinen would make the road easier to walk when they continued on their journey.’

The photo shows curator Leif Løchen (1921–2011) at Syngjarsteinen in Lom. (Photo: Gjermund Kolltveit)

Traditions and beliefs

Traditions, stories, legends, and place names make sense of the ringing stones from a cultural viewpoint, and we are very interested in documenting all available folklore connected to the stones. Everything is valuable. The stories seem to vary. Some people remember that they as children stopped when they passed and struck a ringing stone for fun. Others tell that people ringed the stones to warn the underearthly beings ‘here we come!’ Some tell about elves and other creatures that live inside the rocks and make them sing. A legend says that Saint Olav once stopped and found a large stone to which he tied his horse, and after this the stone got its ringing sound.

About Dønnsteinen in Lyngdal, Buskerud, it is said that an angry jutul at Lågliåsen became unfriendly with a man in Lyngdal. When the man got married, the giant threw this stone at the bridal party. The stone got the cup marks from the jutul’s fingers. The name Dønnsteinen is explained in an old source, saying that ‘when you strike it, there is a rumble in it’. Dønne comes from the Norse verb dynja, which means thunder, rumble, resonate or make sound.

From Aga in Hardanger, the local legend says that a girl is trapped inside the Klokkesteinen. Only the church bells in Ullensvang Church, on the other side of the fjord, can let her out. Another story from the same place is a memory from reality about Sveins-Anna, an elderly woman from the village, who every Christmas night went down to Klokkesteinen. There she stood and listened to the bells from Ullensvang Church, when they called in for Christmas. We do no know more than this, and the story is not directly about the stone or the sound of the stone, but about the church bells. Perhaps Klokkesteinviki, the area around the stone, was an important and perhaps sacred place for Sveins-Anna. There is a clear connection from this story to legends about other klokkesteiner (bell stones) that are not ‘real’ sonic, ringing stones. Legends often tell of stones that will turn or crack if they ‘hear’ the sound of church bells from a particular church.

In recent times we know that people have tapped ringing stones for fun, out of sheer fascination with the sound, and to explore the sonic qualities. Many stones give different sounds and different pitches depending on where you strike.